It would be a reasonable observation that Australian and international machine safety standards have been in a constant state of flux for the last decade, maybe even longer. To be fair much of this is the result of significant effort to harmonise regulations, codes of practice and standards across industries and safety applications. No one would challenge the reasonable standpoint that it doesn’t make sense that a high severity hazard in one industry is unacceptable, but another industry somehow finds it tolerable. To a large extent this is what the change in standards has been about, coupled with the move towards more performance based, rather than prescriptive design practices.

This leads to the situation in which existing plant with machine safety applications, that have operated over the last twenty years, will likely have equipment that has been installed against a standards environment that some operators and maintainers would be forgiven as describing as a moving target. Putting all that behind us, how should operators and maintainers look at their plant going forward to get their house in order.

First, I think that I should deal with the misconception that “if I don’t touch it” I don’t have to do anything. The Australian regulatory environment is very short on exemptions or hall passes in the Workplace Health and Safety space. Duty of care requirements have existed in Australian common law for more than fifty years but were further formally enshrined in the changes in the Australian WH&S regulatory environment in 2011. In short, the “if I don’t touch it” approach will be a very weak defence if you have a significant incident. That being the case, what would I suggest existing plant owners do with regards to existing equipment that has been installed on plant to control or mitigate risk.

Let me start by clarifying that the scope of this discussion is limited to the two most common machine safety applications which are typically just one part of comprehensive machines guarding.

These are:

- The humble guard interlock – this is where a guard in not permanently fixed and can be moved by the operator to gain access to the hazardous parts of the machine. The physical movement of the guard will “interlock” energy sources within the machine to prevent the operator from being harmed. (This is not to be confused with “lock-out” of energy sources.)

- The presence sensing interlock – this is where a sensor will determine if an operator is present in a location where they could be harmed, and the sensing of the presence will “interlock” energy sources within the machine in much the same way as the guard interlock.

These should be easy enough to distinguish but there are good resources explaining machine guarding available at Queensland Worksafe that provide clarification.

More complex functions that require more complicated voting or sequencing are beyond the scope of this discussion. As a generalization they need to be treated differently as they may use application software in their implementation.

Before going further, let me address the CAT versus PL discussion. Those familiar with machine safety applications will know that there has been a slow transition from what was called “the Category or CAT system” to the Performance Level (PL) system. Both systems were used to define the ability of safety-related parts of electrical and electronic systems to perform a safety function under foreseeable adverse conditions. Without getting into a detailed discussion about the history and merits of either system, I would offer the following advice. As the name would suggest, the Performance Level system is more substantially aligned with the new doctrine of designing the machine safety function to match the level of risk. While AS 4024 – Safety of Machinery, for practical reasons, leaves the door open for equipment that has been designed using the Category System approach, I would suggest for consistency and to avoid future issues, unless the plant is at end of life, that the PL approach as described in AS4024 be used.

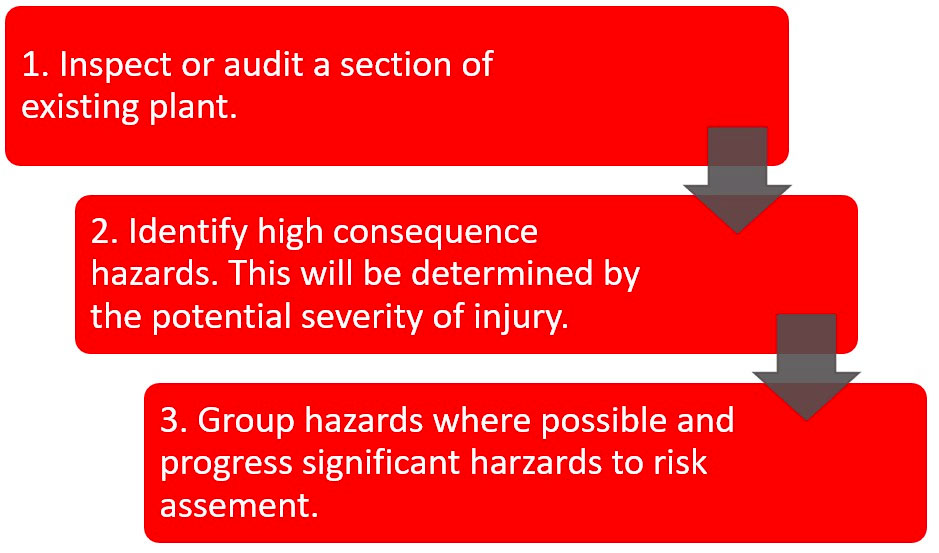

A good place to start when looking for guidance is the “Managing risk of plant in the workplace; code of practice 2013”. This is the intended guide for engineers and designers that are looking at implementing machine safety functionality in new plant. However, it can be applied to existing plant as well. Rather than strictly following the workflow described in the code of practice, I would suggest the following the deviation in the workflow shown below:

Operations and maintenance are by nature time poor. I would suggest a focus on known issues, near misses or incidents. Stepping through the plant in a methodical manner will reduce the chance of missing functions. Once you start the risk assessment process, it should become apparent where your sensitive spots are and where you should direct your effort. The level of risk will be a combination of the severity of injury, the frequency of the interaction with plant (exposure) and the ability of personnel to ergonomically avoid the hazard.

I would strongly suggest creating a unique identifier for each safety related control function to allow them to be identified within the plant.

This will help with:

- Determining where each safety related control function is within the overall machine safety lifecycle process. (What steps have or have not been done.)

- Tracking changes and modifications.

- Tracking of reliability and replacement of components. (Failure data)

- Tracking testing and remedial actions.

- Tracking of incidents or failure on demand.

The last twenty years have seen significant and more or less continual improvement in equipment manufacturers’ machine guarding and equipment safety. The existing machine safety functions in your plant should be working well because they were designed by conscientious engineers and designers as you would hope they were. The onus sits with the plant owner to make sure that these control measures are suitable, robust, have been tested and are specifically treating the risk. There are plenty of good information resources available in this space and there are specialists that can guide you through the process. Even though the task may seem enormous on some larger plants, it will, like any other undertaking, be best tackled one step at a time.

But please take that first step.